that autumn the chancelleries of europe happened to be rather less egotistic than usual, and the english and american publics, seeing no war-cloud on the horizon, were enabled to give the whole of their attention to the balloon sent up into the sky by mr. onions winter. they stared to some purpose. there are some books which succeed before they are published, and the commercial travellers of mr. onions winter reported unhesitatingly that a question of cubits was such a book. the libraries and the booksellers were alike graciously interested in the rumour of its advent. it was universally considered a 'safe' novel; it was the sort of novel that the honest provincial bookseller reads himself for his own pleasure and recommends to his customers with a peculiar and special smile of sincerity as being not only 'good,' but 'really good.' people mentioned it with casual anticipatory remarks who had never previously been known to mention any novel later than john halifax gentleman.

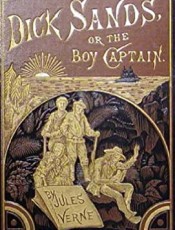

this and other similar pleasing phenomena were, of course, due in part to the mercantile sagacity of mr. onions winter. for during a considerable period the anglo-saxon race was not permitted to forget for a single day that at a given moment the balloon would burst and rain down copies of a question of cubits upon a thirsty earth. a question of cubits became the universal question, the question of questions, transcending in its insistence the liver question, the soap question, the encyclopædia question, the whisky question, the cigarette question, the patent food question, the bicycle tyre question, and even the formidable uric acid question. another powerful factor in the case was undoubtedly the lengthy paragraph concerning henry's adventure at the alhambra. that paragraph, having crystallized itself into a fixed form under the title 'a novelist in a box,' had started on a journey round the press of the entire world, and was making a pace which would have left jules verne's hero out of sight in twenty-four hours. no editor could deny his hospitality to it. from the new york dailies it travelled viâ the chicago inter-ocean to the montreal star, and thence back again with the rapidity of light by way of the boston transcript, the philadelphia ledger, and the washington post, down to the new orleans picayune. another day, and it was in the san francisco call, and soon afterwards it had reached la prensa at buenos ayres. it then disappeared for a period amid the pacific isles, and was next heard of in the sydney bulletin, the brisbane courier and the melbourne argus. a moment, and it blazed in the north china herald, and was shooting across india through the columns of the calcutta englishman and the allahabad pioneer. it arrived in paris as fresh as a new pin, and gained acceptance by the paris edition of the new york herald, which had printed it two months before and forgotten it, as a brand-new item of the most luscious personal gossip. thence, later, it had a smooth passage to london, and was seen everywhere with a new frontispiece consisting of the words: 'our readers may remember.' mr. onions winter reckoned that it had been worth at least five hundred pounds to him.

but there was something that counted more than the paragraph, and more than mr. onions winter's mercantile sagacity, in the immense preliminary noise and rattle of a question of cubits: to wit, the genuine and ever-increasing vogue of love in babylon, and the beautiful hopes of future joy which it aroused in the myriad breast of henry's public. love in babylon had falsified the expert prediction of mark snyder, and had reached seventy-five thousand in great britain alone. what figure it reached in america no man could tell. the average citizen and his wife and daughter were truly enchanted by love in babylon, and since the state of being enchanted is one of almost ecstatic felicity, they were extremely anxious that henry in a second work should repeat the operation upon them at the earliest possible instant.

the effect of the whole business upon henry was what might have been expected. he was a modest young man, but there are two kinds of modesty, which may be called the internal and the external, and henry excelled more in the former than in the latter. while never free from a secret and profound amazement that people could really care for his stuff (an infallible symptom of authentic modesty), henry gradually lost the pristine virginity of his early diffidence. his demeanour grew confident and bold. his glance said: 'i know exactly who i am, and let no one think otherwise.' his self-esteem as a celebrity, stimulated and fattened by a tremendous daily diet of press-cuttings, and letters from feminine admirers all over the vastest of empires, was certainly in no immediate danger of inanition. nor did the fact that he was still outside the rings known as literary circles injure that self-esteem in the slightest degree; by a curious trick of nature it performed the same function as the press-cuttings and the correspondence. mark snyder said: 'keep yourself to yourself. don't be interviewed. don't do anything except write. if publishers or editors approach you, refer them to me.' this suited henry. he liked to think that he was in the hands of mark snyder, as an athlete in the hands of his trainer. he liked to think that he was alone with his leviathan public; and he could find a sort of mild, proud pleasure in meeting every advance with a frigid, courteous refusal. it tickled his fancy that he, who had shaken a couple of continents or so with one little book; and had written another and a better one with the ease and assurance of a novelist born, should be willing to remain a shorthand clerk earning three guineas a week. (he preferred now to regard himself as a common shorthand clerk, not as private secretary to a knight: the piquancy of the situation was thereby intensified.) and as the day of publication of a question of cubits came nearer and nearer, he more and more resembled a little jack horner sitting in his private corner, and pulling out the plums of fame, and soliloquizing, 'what a curious, interesting, strange, uncanny, original boy am i!'

then one morning he received a telegram from mark snyder requesting his immediate presence at kenilworth mansions.