cuttings.

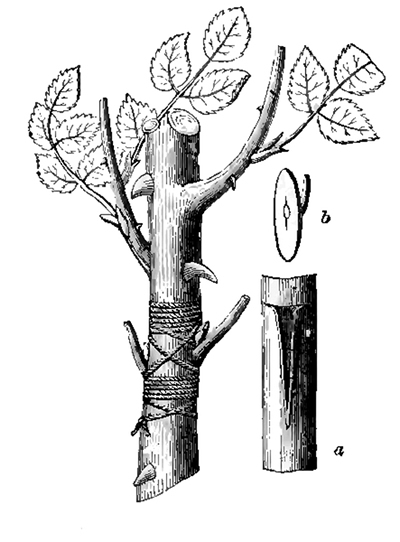

this mode of propagation, although possible with all roses, is more difficult with those that bloom only once in the season. it is most applicable to the smooth-wooded kinds, as the bengal and its sub-classes, and the boursault, microphylla, rubifolia, etc. many of the perpetuals and bourbons are propagated with facility by the same mode. for propagation in the open ground, cuttings should be made in the autumn, or early part of winter. they should be made of wood of the growth of the season, and about six inches long. the lower end should be cut square, close to a bud, and they can then be planted thickly, two-thirds of their length in sand, in a light and dry cellar. here a callus will be formed on the bottom of each cutting during the winter, and on being planted out in the spring, they will immediately throw out roots. they should be planted as early as possible in the spring, in a light sandy loam, with one-third of their length and at least one bud above the surface of the ground. they should be planted very early in the spring, because, if left until late, the power of the sun is too much for them. the earth should be trodden down very tight about them, in order, as much as possible, to exclude the air. if the weather is dry, they should be carefully watered in the evening. where it is inconvenient to make the cuttings in the fall or early in the winter, they can be made in the spring; but in consequence of having to form the callus, they will require a much lighter soil than will afterward be desirable for their growth, and they will also be much[pg 114] later in coming on. this mode of open propagation answers very well for some of the smooth-wooded roses of the more robust growing varieties, like the boursault and rubifolia; but for the delicate bengals, the best mode is pot propagation. for this purpose, small pots can be used, filled with equal parts of mould and sand, or peat and sand. about the middle of autumn, cuttings of the same season’s growth are taken off with two to four buds, cutting off one or two of the lower leaves, and cutting off the wood smooth and square close to the eye, as in figure 8. these cuttings can be inserted in the pot, leaving one eye above the surface. it should then be slightly watered to settle the soil firmly around the cuttings, and then placed in a cold frame, or on the floor of a vinery, in which no fire is kept during winter. early in the spring the pot should be placed in a house with a moderate temperature, kept perfectly close, and sprinkled every morning with water a little tepid. now, as well as during the autumn, they should be shaded from the too bright glare of the sun. in about a fortnight, and after they have formed a third set of leaves and good roots, a little air can be given them; and after being thus hardened for a week, they can be repotted into larger pots. in order to ascertain when they are sufficiently rooted, the ball of earth can be taken out of the pot, by striking its inverted edge lightly against some body, at the same time sustaining the ball of earth[pg 115] by the hand, the cutting being passed between two of the fingers a little separated. if well rooted, the fibres will be seen on the outside of the ball of earth. they can then be placed in a cold frame, or anywhere under glass, to be planted out the latter part of spring, or retained for pot culture. where hot-bed frames are not convenient, or the amateur wishes only to experiment with one or two cuttings, he can use a tumbler, or any kind of close glass covering.

fig. 8.—a rose cutting.

where roses are forced into bloom the latter part of winter, cuttings can be taken from them immediately after the bloom is past; and they will also succeed if taken from plants in the open ground immediately after their first bloom. cuttings of the everblooming roses will all strike at any time during the summer, but they succeed much better either in the autumn, or after their first bloom. the heat of our midsummer sun is so great upon plants forced in the house, that cuttings often fail at that time. when a cutting is made near the old stem, it is better to take with it a portion of the old wood, which forms the enlarged part of the young branch. where the cuttings are scarce, two buds will answer very well—one below the surface; and, in some cases, propagation has been successful with only one eye. in this case they are planted up to the base of the leaf in pots of sand, similar to that used in the manufacture of glass, and the eye is partially covered. they are then subject to the same treatment as the others, and carefully shaded; they will thus root easily, but require a long time to make strong plants.

some years since, lecoq, a french cultivator, conceived the idea of endeavoring to propagate roses by the leaf. he gathered some very young leaves of the bengal rose, about one quarter developed, cutting them off at their insertion, or at the surface of the bark. he planted these in peat soil, in one-inch pots, and then plunged the pots[pg 116] into a moderate heat. a double cover of bell glasses was then placed over them, to exclude the air entirely, which course of treatment was pursued until they had taken root. the shortest time in which this could be accomplished was eight weeks, and the roots were formed in the following manner. first, a callus was formed at the base of the leaf, from which small fibres put forth; a small bud then appeared on the upper side (figure 9); a stalk then arose from this bud, which finally expanded into leaves and formed a perfect plant.

fig. 9.—leaf cutting.

an english writer remarks, that “the leaves or leaflets of a rose will often take root more freely than even cuttings, and in a much shorter time, but these uniformly refuse to make buds or grow.”

this experiment is certainly very curious, and evinces how great, in the vegetable kingdom, are the powers of nature for the maintenance of existence, and is one of those singular results which should lead us to make farther experiments with various parts of plants, and teach us that in horticulture there is yet a wide field for scientific research.

a favorite mode of propagation with some nurserymen is from soft wood of plants forced in the winter. many fail entirely in this for want of knowledge of the right condition in which the wood should be before cutting, a condition which cannot be described on paper. some varieties, like persian yellow, will not strike at all, or with great difficulty in this way.

the plants from which these cuttings are to be taken should be prepared and treated as in the preceding chapter. in february and march the cuttings are made and inserted in sand, either in pots or benches, in a house of[pg 117] the same temperature as that in which the parent plant has grown. these pots or benches would be better covered with glass, but it is not essential. after the cuttings have rooted, they can be potted into small pots, and placed in a house of moderate temperature. about the middle of may they can be taken out of these pots and planted in the open ground.

by layers.

this mode is more particularly applicable to those roses that bloom only once in the year, and which do not strike freely from cuttings, although it can be equally well applied to all the smooth-wooded kinds. it can be performed at midsummer and for several weeks afterward, and should be employed only in those cases where young shoots have been formed at least a foot long and are well matured. the soil should be well dug around the plant, forming a little raised bed of some three feet in diameter, with the soil well pulverized and mixed with some manure thoroughly decomposed, and, if heavy, a little sand. a hole should then be made in this bed about four inches deep, and the young matured shoot bent down into it, keeping the top of the shoot some three or four inches above the surface of the ground; the angle thus being found, which should always be made at a bud and about five or six inches from the top of the shoot, the operator should cut off all the leaves below the ground. a sharp knife should then be placed just below a bud, about three inches below the surface of the ground, and a slanting cut made upward and lengthwise, about half through the branch, forming a sort of tongue from one to two inches long, on the back part of the shoot right opposite the bud; a chip or some of the soil can be placed in the slit, to prevent it from closing, and the shoot can then be carefully laid in the hole, and pegged down at a point some two[pg 118] inches below the cut, keeping, at the same time, the top of the shoot some three or four inches out of the ground, and making it fast to a small stake, to keep it upright. care should be taken not to make the angle where the branch is pegged at the cut, as the branch would be injured and perhaps broken off; the best place is about two inches below the incision. the soil can then be replaced in the hole, and where it is convenient covered with some moss or litter of any kind. this will protect the soil from the sun and keep it moist, and will materially aid the formation of new roots. these are formed in the same manner as in cuttings; first a callus is produced on those parts of the incision where the bark joins the wood, and from this callus spring the roots, which, in some cases, will have grown sufficiently for the layers to be taken from the parent plant the latter part of the following autumn; in some cases, however, the roots will not have sufficiently formed to allow them to be taken up before another year. the summer is the best period for layering the young shoots. early in the spring, layers can be made with the wood formed the previous year. where it is more convenient, a shoot can be rooted by making the incision as above, and introducing it into a quart pot with the bottom partly broken out. this pot can be plunged in the ground, or if the branch is from a standard, it can be raised on a rough platform. in either case, it should be covered with moss, to protect it from the sun, and should be watered every evening. we recollect seeing in the glass manufactories of paris, a very neat little glass tumbler, used by the french gardeners for this purpose. it held, perhaps, half a pint, and a space about half an inch wide was cut out through the whole length of the side, through which space the branch of any plant was inserted, and the tumbler then filled with soil. when the roots were formed and began to penetrate the soil, they could be easily perceived through the glass.[pg 119] although an incision is always the most certain, and it is uniformly practiced, roots will in many varieties strike easily from the buds; and a common operation in france is simply to peg down the branches in the soil, without any incision; in some cases, they give the branch a sudden twist, which will break or bruise the bark, and facilitate the formation of roots.

some chinese authors state that very long branches may be laid down, and that roots may be thus obtained from all the eyes upon them, which will eventually form as many plants.

vibert, a well-known rose cultivator in france, remarks upon this point: “upon laying down with the requisite care some branches fifteen to twenty-four inches long, of the new growth, or of that of the previous year, and upon taking them up with similar care, after twelve or eighteen months, i found only the first eyes expanded into buds or roots, while the rest had perished. i have seldom seen the fifth eye developed, while i have frequently known the whole branch entirely perish. i speak in general terms, for there are some rare exceptions, and the different varieties of the four-seasons rose may be cited as proof that a great number of eyes of the same branch have taken root.”

this is the opinion of an eminent rose grower; but if, as he states, the monthly damask rose will root freely in this way, many of the smooth-wooded roses would undoubtedly root still more readily, and our rapid growing native rose, queen of the prairies, would very probably throw out roots readily, when treated in this manner. it is worth repeated experiment; for, if rapid growing roses, like some of the evergreen varieties, the greville, and the queen of the prairies, could with facility be made to grow in this way, rose hedges could be easily formed by laying down whole branches, and a very beautiful and effective[pg 120] protection would be thus produced, to ornament our fields and gardens.

suckers.

many roses throw up suckers readily from the root, and often form one of the principal causes of annoyance to the cultivator. for this reason, budding and grafting should always be done on stocks that do not incline to sucker. the dog rose—on which almost all the imported varieties are now worked—is particularly liable to this objection, and it is no unusual thing to see half-a-dozen suckers growing about a single rose-tree. when the health and prosperity of the plant are desired, these should be carefully kept down, as they deprive the plant of a material portion of its nourishment. when, however, they are wanted for stocks, they should be taken off every spring with a small portion of root, which can generally be obtained by cutting some distance below the surface of the ground. they should be planted immediately where they are wanted for budding, and will soon be fit for use. many fine varieties of the summer roses will sucker in this way, and an old plant when taken up will sometimes furnish a large number of thrifty stems, each with a portion of root attached.

budding.

fifty years ago, budding and grafting were very little practiced, excepting with new varieties, that could with great difficulty be propagated in any other way. within that time, however, the practice has been constantly increasing until now, when it is extensively employed in europe, and roses imported from france and england can very rarely be obtained on their own roots. to this mode of propagation, there is one great objection, while the[pg 121] advantages in some varieties are sufficiently great to counterbalance any inconveniences attending the cultivation of a budded or grafted rose. it is generally the case, that the stock or plant on which the rose is budded is of some variety that will throw up suckers very freely, which growing with great luxuriance, will sometimes overpower the variety budded upon it, and present a mass of its own flowers. the purchaser will thus find a comparatively worthless bloom, instead of the rare and beautiful varieties whose appearance he has been eagerly awaiting, and upon the head of the nurseryman will frequently descend the weight of his indignation. this difficulty can, however, be avoided by a very little attention. the shoot of the stock can very readily be distinguished from that of the budded or grafted variety by its growth and foliage, even if the age of the plant will not allow the point of inoculation to be recognized. in passing the plant in his walks, let the owner simply cut away any shoot of this character that may spring from the stock or root. the budded variety thus receiving all the nourishment from the root, will soon grow with luxuriance, and present to the eager expectant as fine a bloom as he may desire—at the expense only of a little observation, and the trouble of occasionally taking his knife from his pocket.

this trouble, however, is such that the plant is in most cases neglected. budded or grafted roses are thus very unpopular in this country, and those on their own roots are deemed the only ones which it is safe to plant.

the practice of budding has brought into cultivation a form of the plant which is highly ornamental, but which can never become very general in this country. the tree rose is an inoculation upon a standard some four or five feet in height, generally a dog rose or eglantine. the tall, naked stem, a greater part of which is unsheltered by any foliage, is exposed to the full glare of our summer sun, and unless protected in some way, will often die out[pg 122] in two or three years. its life can be prolonged by covering the stem with moss, or with a sort of tin tube, provided with small holes, to allow the air to enter and circulate around the stem. this is, however, some trouble; and as many will not provide this protection, a large part of the standard roses imported to this country will gradually die out, and rose bushes be generally employed for single planting, or for grouping upon the lawn.

in budding, there are two requisites: a well-established and thriftily growing plant, and a well-matured eye or bud. the operation can be performed at any season when these requisites can be obtained. in the open ground, the wood from which the buds are cut is generally not mature until after the first summer bloom.

fig. 10.—budding the rose.

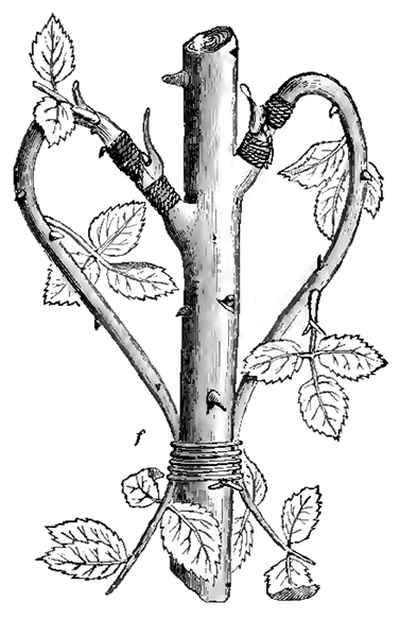

fig. 11.—budding in the branches.

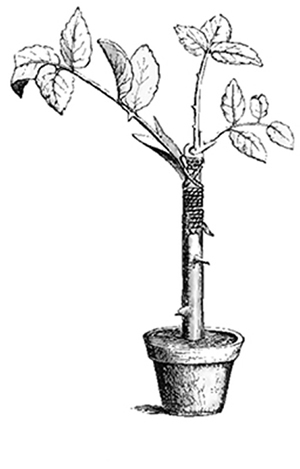

fig. 12.—budding a potted rose.

having ascertained by running a knife under the bark, that the stock will peel easily, and having some perfectly ripe young shoots with buds upon them, the operation can be performed with a sharp knife that is round and very thin at the point. make in the bark of the stock a longitudinal incision of three-quarters of an inch, and another short one across the top, as in a, fig. 10; run the knife under the bark and loosen it from the wood; then cut from one of the young shoots of the desired variety, a bud, as in b; placing the knife a quarter to three-eighths of an[pg 123] inch above the eye or bud, and cutting out about the same distance below it, cutting sufficiently near the bud to take with it a very thin scale of the wood. english gardeners will always peel off this thin scale; but in our hot climate, it should always be left on, as it assists to keep the bud moist, and does not at all prevent the access of the sap from the stock to the bud. the bud being thus prepared, take it, by the portion of leaf-stalk attached, between the thumb and finger in the left hand, and, with the knife in the right, open the incision in the bark sufficiently to allow the bud to be slipped in as far as it will go, when the bark will close over and retain it. then take a mat-string, or a piece of yarn, and firmly bind it around the bud, leaving only the petiole and bud exposed, as in c, fig. 10. the string should be allowed to remain for about two weeks, or until the bud is united to the stock. if allowed to remain longer, it will sometimes cut into the bark of the rapidly growing stock, but is productive of no other injury. it is the practice with many cultivators to cut off the top of the stock above the bud immediately after inoculation. a limited acquaintance with vegetable physiology would convince the cultivator of the injurious[pg 124] results of this practice, and that the total excision of the branches of the stock while in full vegetation must be destructive to a large portion of the roots, and highly detrimental to the prosperity of the plant. a much better mode is to bend down the top, and tie its extremity to the lower part of the stock. several days after this is done, the bud can be inserted just below the sharpest bend of the arch. when the buds are to be placed in the branches of a stock, as in fig. 11, the top of the main stem can be cut off, and the branches arched over and tied to the main stem, as at f; the bud is then inserted in each branch, as at c. the circulation of the sap being thus impeded by the bending of the branches, it is thrown into the inoculation, and forms then a more immediate union than it would if the branches were not arched. after the buds have become fairly united to the stock and have commenced growing, the top can be safely cut off to the bud, although it would be still better to make the pruning of the top proportionate to the growth of the bud; by this means, a slower, but more healthy vegetation is obtained. when the buds are inserted very late in the season, it is better not to cut off the top of the stock or branches until the following spring, and to preserve the bud dormant. if[pg 125] allowed to make a rapid growth so late in the season, there would be great danger of its being killed by frost. european cultivators are very fond of budding several varieties on one stock, in order to obtain the pretty effect produced by a contrast of color. this will only answer where great care is taken to select varieties of the same vegetating force; otherwise one will soon outstrip the others, and appropriate all the nourishment. it is also desirable that they should belong to the same species. when a bud is inserted in a plant in pot, as in fig. 12, the main branches are left, and a portion of the top only cut off, in order to give the bud some additional nourishment.

grafting.

from the pithy nature of the wood of the rose, grafting is always less certain than budding; but it is frequently adopted by cultivators, as budding cannot be relied upon in the spring, and as there is much wood from the winter pruning which would be otherwise wasted. it is also useful for working over those plants in which buds have missed the previous summer.

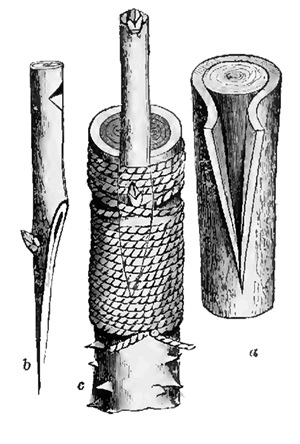

there are several modes of grafting, of which the most generally practiced is cleft-grafting. for this mode, the stock is cut off at the desired height with a sharp knife, either horizontally, or slightly sloping. the cut should be made just above a bud, which may serve to draw up the sap to the graft. the stock can then be split with a heavy knife, making the slit or cleft about an inch long. the cion should be about four inches long, with two or more buds upon it. an inch of the lower part of the cion can be cut in the shape of a wedge, making one side very thin, and on the thick or outer side, leaving a bud opposite to the top of the wedge. this cion can then be inserted in the cleft as far as the wedge is cut, being very careful to make the bark of the cion fit exactly to that of[pg 126] the stock. in order to exclude the air, the top and side of the stock should then be bound with a strip of cloth covered with a composition of beeswax and resin in equal parts, with sufficient tallow to make it soft at a reasonably low temperature. in the course of two or three weeks, if every thing is favorable, the cion will begin to unite, and will be ready to go forward with advancing vegetation. when the stock is sufficiently large, two cions can be inserted, as in fig. 13.

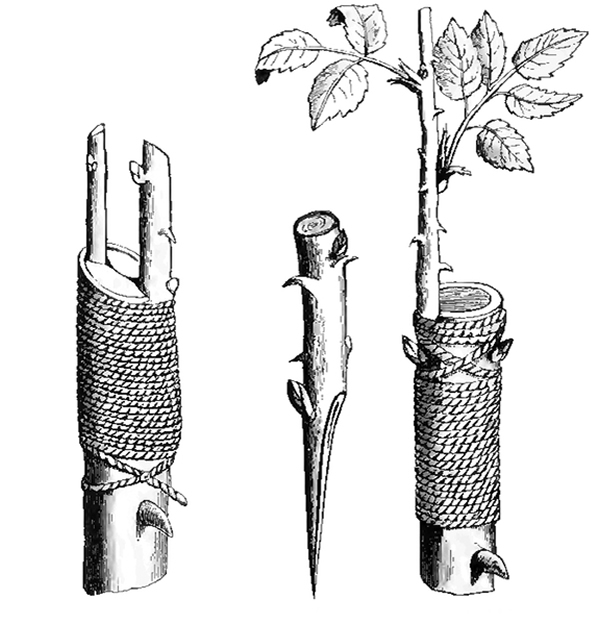

fig. 13.—cleft grafting. fig. 14.—whip grafting.

whip-grafting is performed by cutting a slice of bark with a little wood from the side of a stock about an inch and a half long, and then paring a cion of the usual length down to a very thin lower extremity, as in fig. 14. this cion can then be accurately fitted on to the place from which[pg 127] the slice of bark and wood is taken. the whole can then be bound around with cotton cloth, covered with the composition described before. in all grafting it should be borne in mind, that it is essential for the bark of the cion and that of the stock to touch each other in some point, and the more the points of contact, the greater will be the chance of success.

rind-grafting is also sometimes practiced, but is more uncertain than the former, as the swelling of the stock is very apt to force the cion out. this mode must be practiced when the bark peels easily, or separates with ease from the wood. the top of the stock must be cut off square, and the bark cut through from the top about an inch downward. the point of the knife can then be inserted at the top, and the bark peeled back, as in a, fig. 15. it is desirable, as before, that a bud should be left on the other side of the stock, opposite this opening; and the french prefer, also, to have a bud left on the outside of the part of the cion which is inserted. the cion should be cut out and sloped flat on one side, as in b, fig. 15; then inserted in the stock between the bark and wood, as in c, and bound with mat-strings, or strips of grafting cloth.

fig. 15.—rind grafting.

the french have another mode of grafting stocks about the size of a quill or the little finger. it is done by placing the knife about two inches below a bud which is just on the point of starting, and cutting half way through the stock, and two inches down, as in fig. 16. the cion[pg 128] is then placed in the lower part of this cavity, in the same manner as with cleft grafting. this mode is called aspirant, from the bud above the incision, which continues to draw up the sap, until the development of the cion. when the cion has grown about two inches, the top of the stock is cut off and covered with grafting wax. this mode is not always successful, as the sap sometimes leaves the side of the stock which has been partly cut away and passes up the other side.

fig. 16.

the french have also a mode of grafting, which they call par incrustation, and which is performed in the spring, as soon as the leaf-buds appear. a cion with a bud adhering to the wood is cut in a sort of oval shape, and inserted in a cavity made of the same shape, and just below an eye which has commenced growing. it is then bound around with matting, as in budding. this is a sort of spring budding, with rather more wood attached to the bud, than in summer budding. it is very successfully practiced by various cultivators in the vicinity of paris. there is still another mode sometimes practiced in france, which owes its origin to a cultivator named lecoq. a small branch is chosen, which is provided with two buds, one of them being on the upper part, and the other near its larger end. a sidelong sloping cut is made all along its lower half, the upper being left entire. when the cion is thus prepared, its cut side is fitted to the side of the stock under the bark, which has been cut and peeled back. it is then bound around with mat-strings or grafting cloth in the usual way. this mode has a peculiar merit; should the upper bud not grow, the lower one rarely fails, and develops itself as in common budding.

cleft and whip-grafting is also practiced occasionally upon the roots of the rose, and succeeds very well with[pg 129] some varieties. these modes of grafting can all be more successfully practiced on stocks in pots in green-houses with bottom heat and bell glasses. we have given thus concisely, and, we hope, clearly, the various modes of budding and grafting with which we are acquainted. they may be sufficient to enable the amateur to amuse his leisure hours, though his success may not entirely meet his expectations. simple as these operations are, they require a kind of skill, and, if we may so call it, sleight-of-hand, which is only attained by constant practice upon a great number of plants.