submarines in action

submarines have two great advantages over all types of surface warships; they can become invisible at will—or sufficiently invisible to make gun or torpedo-practice, except at very close quarters, almost entirely useless—and they can, by sinking, cover themselves with armour-plate of sufficient thickness to be absolutely shell-proof. these are the two main points in favour of the submarine. there are, however, many minor features. although submarines are known in the naval services as “daylight torpedo-boats,” for their greatest value lies in their ability to perform the same task in the “light” as the ordinary surface torpedo-boats and destroyers can do under 125cover of darkness or fog—that of creeping up close to an enemy, and launching a torpedo unobserved—they have been given, during recent years, so much greater speed, armament, and range of action, that they can no longer be looked upon as small boats just suitable for daylight torpedo attack in favourable circumstances. their surface speed has been increased from 10 to 20 knots, making them almost as fast as the surface torpedo-boat. this, combined with man?uvering powers and general above-water invisibility, has enabled them to take over the duty of the surface torpedo-boat—that of delivering night-attacks on the surface. after nightfall a submarine attack is almost impossible owing to the periscope—the eyes of the submarine—being useless in the dark.

the increase in the armament of the submarine—from the single bow torpedo tube with two torpedoes of short range and weak explosive charge, to the four bow and two stern tubes with eight or ten 126torpedoes of long range and high explosive charge—has greatly increased their chances of successful attack on surface warships, first, by giving them four or six shots ahead, then the possibility, in the event of all these torpedoes missing, of a dive under the object of attack, and two more shots at close range from the stern tubes (still retaining two torpedoes); and, secondly, by increasing the distance from which the first projectile can be launched, owing to the increased range of the modern torpedo. there are also the advantages derived from the battery of quick-firing guns installed on the decks of modern submarines. although at the present time these guns are only of small power they nevertheless afford a means of defence—and even of attack under favourable circumstances—against hostile surface torpedo-boats, destroyers, and air-craft. in fact, a flotilla of submarines could undoubtedly now give a very good account of 127itself if attacked either on the surface or when submerged by one or two prowling destroyers. the increase in the power of the guns carried by submarines, which will certainly come soon, will enable this type of craft to take up the additional duties of the destroyer—that of clearing the seas of hostile torpedo-boats and carrying out advanced scouting—for which work their ability to travel submerged and in a state of invisibility for distances of over 100 miles makes them eminently suitable.

the enormous increase in the size and range of action of submarines, combined with the improvements effected in the surface cruising qualities, have enabled these vessels to be taken from the “nursery” of harbour and coast defence and placed with the sea-going flotillas and battle-fleets. in the short period of ten years the tonnage of submarines has risen from 100 to over 1,000 tons, and the range of action from 400 miles at economical speed to 1285,000 miles. exactly what this means is more easily realized when it is stated that the earlier types of submarines could scarcely cross the english channel and return without taking in supplies of fuel, and in rough weather were forced to remain in harbour, whereas the modern vessel can go from england to newfoundland and back without assistance, and can remain at sea in almost any weather, as was first demonstrated by the successful voyage of the british submarines a.e.1 and a.e.2 to australia, and has since been proved by the operations of the british submarine flotilla in the north sea.

in addition to the cruising range there is, however, the question of habitability. in this respect the progress has been equally as rapid. in the older boats no sleeping accommodation was provided for the crew, and food supplies and fresh water sufficient only for a few days were carried. in the 129latest british, french and german vessels proper sleeping and messing accommodation is provided, and supplies of all kinds and in sufficient quantity to last a month are carried. although work on these craft is still very cramping for the crew, the increase in the deck space and in the surface buoyancy has greatly minimised the discomforts of service in the submarine flotilla.

with regard to safety, it has already been shown that a submarine is only held below the surface by the power of her engines and the action of the water on her diving-rudders. this means that in the event of anything going wrong inside the vessel she would automatically rise to the surface; but should the hull be pierced in any way, either by shot or by collision, and an overwhelming inrush of water result—overcoming the buoyancy quickly obtained by blowing out the water-ballast tanks—then the vessel must inevitably sink, and the 130question of whether or not the crew can save themselves becomes a problem to which no definite answer can be given, although a special means is provided in all modern vessels belonging to the british navy. speaking generally, it may, however, be said that if the disaster occurs suddenly, and the vessel sinks into very deep water rapidly, the chances of life-saving are extremely small; but if the water is comparatively shallow, as along the coast (100 to 150 feet), the likelihood of many of the crew being able to save themselves with the aid of the special escape helmets and air-locks is fairly good.

we now come to the most important improvement made in the fighting qualities of these vessels since first they came into being, viz. the wonderful increase in the surface and submerged speed. in the older craft the surface speed did not exceed 8 to 10 knots an hour, whereas it now amounts to 16 to 20 knots, and the submerged speed has risen from 5 knots to 10 to 12 knots. it is a little difficult 131for any but a naval man to realize exactly what this increase in the speed of submarines really means, and it is equally as difficult to adequately describe it here in non-technical language. it is a mere platitude to say that in order to attack a surface warship the submarine must first get within torpedo range of it; and yet it is on this very point that the strategy and tactics of submarine warfare revolve. a clever naval tactician once described the submarine as a “handicapped torpedo-boat.” the two points on which he based this opinion were—the (then) slow speed of these vessels compared with that of the surface warship, and its almost total blindness when submerged. these two defects were for some years the principal drawbacks of all the submarines afloat; but since that naval expert pronounced submarines to be “handicapped torpedo-boats,” great changes, great improvements have been made. the speed of the submarine has increased by over 100 per cent., and they have been given 132longer and wider range of vision by the introduction of two and three improved periscopes instead of one elementary instrument. nevertheless, the speed difficulty is still a very real one, as will readily be seen when it is taken into consideration that the speed of a submarine when attacking submerged is frequently only half, or even a third, of that of her enemy. in order to more clearly illustrate this and lift for a moment the veil of secrecy which enshrouds the methods of attack adopted by this type of craft, it will be necessary to describe what is known as the right-angle attack.

attacking at right angles.

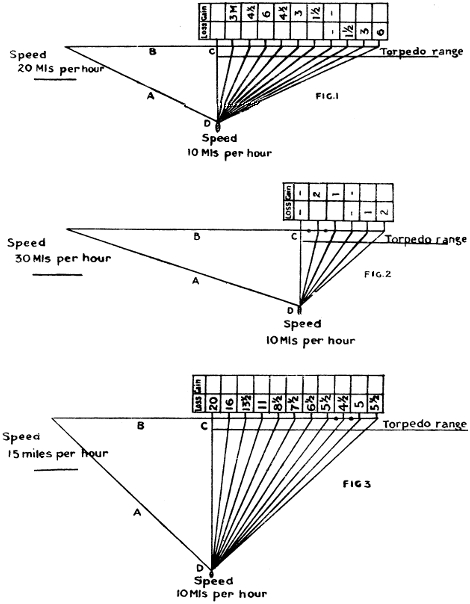

the difficulty of attacking a surface warship steaming at right angles to the course of the submarine will be clearly understood by referring to the following diagrams. the first shows an attack on a warship travelling at 20 miles an hour, such as a big battleship or a cruiser 133any increase in the speed of the surface vessel not only adds to the difficulty of the attacking submarine, but also the direction from which the attack must be made. this feature is shown in the second diagram, which illustrates a submarine attack on a vessel steaming at 30 miles an hour, such as a fast destroyer or fleet scout. on the other hand, a decrease in the speed of the on-coming surface vessel tends to either make easier the task of the attacking submarine, or else to increase the distance from which the attack can be delivered. this is shown in the third diagram, which assumes the speed of the surface vessel to be only 15 miles an hour, such as a merchantman, troopship, food-ship, collier, or old warship.

right-angle attack by submarines.

fig. 1 represents a submarine attacking a hostile warship (or fleet) steaming at 20 (statute) miles an hour. “a” is the line of vision. the submarine sights the warship at a distance of just over 11 miles on her port bow. “b” shows the hostile 134vessel’s course, which is 10 miles to point marked “c,” and each division beyond equals 1 mile.

directly the submarine, which is assumed to be lying in an awash condition, sights the object of attack, she totally submerges and steers forward at a speed of 10 miles an hour. the loss, and gain, of the submarine on the different courses, can be seen in the table above the chart.[7]

the spaces between the black dots show the most favourable points of attack. it will be noticed in the table that both vessels are equal at point “c,” but for many reasons this is not the best point of attack. the gain of about six minutes on the longer course enables the submarine not only to man?uvre into the best possible position for the attack, but 135also to discharge more than one torpedo if necessary.

fig. 2 shows the extreme limit at which a submarine could, with reasonable chances of success, attack a destroyer, or other vessel, steaming at 30 (statute) miles an hour, having sighted her at a distance of 16 miles in the position shown by the line of vision “a.”

the distance to “c” is 15 miles for the surface vessel, and 5 miles for the submarine. here, again, the two vessels would be equal; but the most favourable point of attack is shown by the two black dots—where the submarine has gained two minutes.

fig. 3.—the submarine sights the object of attack at a distance of 14?? miles, in the position shown by the line of vision “a.” the surface vessel has a speed of only 15 miles an hour (merchantman). in this case the surface vessel accomplishes the 10-mile journey along course “b”—arriving at point “c” 20 minutes in advance of the 136submarine. the table shows how the submarine, by changing her course and “throwing” the surface vessel on her beam, gradually reduces the loss, until, at the point marked with the two black dots, she is but 4?? minutes behind. at this distance she could fire her torpedoes at long range, with some likelihood of success.

although these charts show approximately the extreme limits of the right-angle attack, a submarine could, of course, proceed for some distance on the surface at a much faster speed; but considering the rate at which the two vessels would be approaching each other, the submarine which attempted it would run considerable risk of being detected, and thus destroy her chances of a successful attack. considering also the time lost in sinking from the “light” to the totally submerged condition, in coming to close quarters, the gain in speed would not amount to as much as may at first seem probable.[8]

137these charts are drawn and calculations made assuming the following points:—

(1)

the weather—fine and bright.

(2)

not taking into consideration strong tides, currents, etc.

(3)

the enemy on the alert.

(4)

submarine waits at point “d” in an awash condition.

(5)

owing to 1, 2, and 3 above, the submarine travels from point “d” in all courses in a submerged condition.

the most favourable position for a submarine flotilla is to man?uvre close up to a fleet at anchor, or to get within 1,000 yards of a fleet—steaming across its course; but both of these ideal positions for attack are extremely difficult to obtain, and consequently in all the less favourable positions speed is the deciding factor. strategems will undoubtedly play an important part in submarine warfare. an example of this has already been afforded when the 138german submarines resorted to the dishonest trick of laying in wait behind a trawler engaged in laying mines, over which the flag of a neutral state had been hoisted as a blind. this resulted in the loss of three british cruisers with over 1,000 lives. it would, however, be quite in accord with the rules of civilised warfare for a submarine to shelter behind a “decoy”; to attack simultaneously with a seaplane; or to approach an enemy behind one of its own merchant ships.

the porpoise dive.

the man?uvre known as the “porpoise dive” is merely the sudden rising of a submarine in order to enable her commander to get a better view of the surface than that afforded by the periscope. the submarine on approaching the object of attack rises quickly to the surface by the action of her horizontal rudders, then dives again, only remaining above water for a few seconds to enable her commander 139to get a glimpse of the enemy, and to take bearings. the submarine can then get within torpedo-range, with simply the tiny periscope projecting from the surface. this man?uvre is now seldom necessary, owing to the long and wide range of vision of the two or three periscopes fitted in modern submarines.

difficulty of the fixed torpedo tube.

with the exception of one or two vessels, which it would be unwise to specify, all the submarines engaged in the present war have what are called fixed submerged tubes. this means that the tubes from which the torpedoes are discharged are fitted inside the submarine on a line with the centre of the boat, and cannot be moved or aimed in any way apart from the boat itself. it therefore becomes necessary for the submarine to be aligned by the steering rudders on the object of attack before the torpedoes can be discharged. in simpler vein, torpedoes 140can only be fired by a submarine straight ahead or straight astern. hence a submarine, with a hostile warship coming up on its beam, is compelled to turn and face its opponent (or turn its stern towards her) before delivering an attack.

submarine flotilla v. surface fleet.

it is absolutely necessary for submarines acting in company to have each its allotted task; and for a wide space of water to be left between each boat; as it is impossible, at present, for one submarine to know the exact position of another when both vessels are submerged. therefore, if each boat was not previously instructed how to act, there would not only be the likelihood of the greater portion of an attacking flotilla firing their torpedoes at one or two vessels of the hostile fleet and allowing the remainder either to escape or to keep up a heavy and dangerous fire unmolested, but also of collision and of torpedoeing each other 141by accident. there is no means of inter-communication between submarines when submerged, and a battle between submarines is almost impossible.

surprise attack.

in this case invisibility is the element of success. admiral sir cyprian bridge, g.c.b., in a letter to the author once said: “when submerged the concealment of the submarine is practically perfect. if she has not been sighted up to the moment of diving, she will almost certainly reach, unobserved, the point at which she can make her attack.” and this opinion—shared for many years by all experts—has been amply proved in the present war.

a submarine must, however, blend with the surrounding sea in its ever-varying colours, lights and shades, in order that she may be as invisible as possible when cruising on the surface. the french naval authorities experimented off toulon with a luminous paint of a 142sea-green colour; but this, although causing the hull to be almost totally invisible in certain weather, was found to be useless, as, on a bright day with a blue sky, the green showed up clear against the bluish tint of the surrounding sea. after many months of experimenting, a pale, sea-green, non-luminous paint was chosen as the best colour for french submarines. the british admiralty also carried out a few experiments in this direction, and came to the conclusion that a dull grey was the most invisible shade. the german authorities decided in favour of a grey-brown.

when travelling submerged, with only the thin periscopic tube above the surface, it is almost impossible to detect the approach of a submarine before she gets within torpedo range; and when cruising on the surface she is equally as invisible at a distance of a few miles. these qualities enable the submarine in nearly all cases where her speed permits, to effect a surprise attack on a hostile battleship 143or cruiser when not closely screened by fast destroyers, whose duty it is to be ever on the watch for submarines.

as to the tactics which would be employed by a submarine (or flotilla) in attacking a hostile warship (or fleet), it is impossible to say, for, like the impromptu attacks of all “mosquito craft,” the exact method, or man?uvre, is arranged to suit the circumstances, and it is very seldom that two such attacks are carried out alike. generally speaking, however, a hostile warship could be easily sighted, on a fairly clear day, from the flying-bridge of a submarine at a distance of 10 miles; but it would be practically impossible to detect the submarine from the deck of a warship at that distance. on sighting her object of attack the submarine would sink to the “awash” condition, and proceed for from 2?? to 5 miles, as might be deemed expedient. she would then submerge and steer by her periscopes, each of which has a field of vision 144of 60 degrees. he would be a very keen look-out who would be able to detect the few square inches of periscopic tube at a distance of three miles. as this distance lessened, it might be advisable, if the sea was very calm and if the object of attack was stationary, for the submarine to slacken speed, so as to prevent any spray being thrown off by the periscopic tube. assuming, however, that the optical tube was seen by the enemy, it would be extremely difficult to hit it with gun-fire at a distance of one or two miles, or to damage the boat itself, which would probably be immersed to a depth of 12 or 15 feet. at a distance of about 2,000 yards, or just over one mile, the submarine would discharge her first torpedo, following it up with another at closer range from the second bow tube. a rapid dive would then probably be necessary in order to avoid the hail of shot which would plough up the waters around her. if the first two torpedoes missed their mark the submarine might 145either dive completely under the object of attack and then fire her stern tubes at close range, or else man?uvre below the surface for an attack from some other point.

one of the effects produced on fleets or individual warships in war time by the ever present possibility of submarine attack is, however, that they never remain at anchor or even stationary in an exposed position, and seldom—if wise—proceed without destroyers as advance and flank guards. these precautions double the difficulties of a successful submarine attack.