now when we had fairly lighted up, and joe had mixed us a glass of gin and water a piece, i felt that it was a very good time for me to have a talk about the white horse and the scourings. i wasn’t quite satisfied in my mind with all that the old gentleman had told me on the hill; and, as i felt sure that mr. warton was a scholar, and would find out directly if there was any thing wrong in what i had taken down, i took out my note-book, and reminded joe that he had promised to listen to it over his pipe. joe didn’t half like it, and wanted to put the reading off, but mr. warton was very good-natured about it, and said he should like to hear it—so it was agreed that i should go on, and so i began. joe soon was dozing, and every now and then woke up with a jerk, and pretended he had been listening, and made some remark in broad berkshire. he[122] always talks much broader when he is excited, or half asleep, than when he is cool and has all his wits about him. but i kept on steadily till i had got through it all, and then mr. warton said he had been very much interested, and believed that all i had taken down was quite correct.

“what put it into your head,” said he, “to take so much interest in the horse?”

“i don’t know, sir,” said i, “but somehow i can’t think of any thing else now i have been up there and heard about the battle.” this wasn’t quite true, for i thought more of miss lucy, but i couldn’t tell him that.

“when i was curate down here,” said he, “i was bitten with the same maggot. nothing would serve me but to find out all i could about the horse. now, joe here, who’s fast asleep—”

“no, he bean’t,” said joe starting, and giving a pull at his pipe, which had gone out.

“well, then, joe here, who is wide awake, and the rest, who were born within sight of him, and whose fathers fought at ashdown, and have helped to scour him ever since, don’t care half so much for him as we strangers do.”

[123]

“oh! i dwon’t allow that, mind you,” said joe; “i dwon’t know as i cares about your long-tailed words and that; but for keeping the horse in trim, and as should be, why, i be ready to pay—”

“never mind how much, joseph.”

joe grinned, and put his pipe in his mouth again. i think he liked being interrupted by the parson.

“as i was saying, i found out all i could about the horse, though it was little enough, and i shall be very glad to tell you all i know.”

“then, sir,” said i, “may i ask you any questions i have a mind to ask you about it?”

“certainly,” said he; “but you mustn’t expect to get much out of me.”

“thank you, sir,” said i. “a thousand years seems a long time, sir, doesn’t it? now, how do we know that the horse has been there all that time?”

“at any rate,” said he, “we know that the hill has been called, ‘white horse hill,’ and the vale, the ‘vale of white horse,’ ever since the time of henry the first; for there are cartularies of the abbey of abingdon in the british museum which prove it. so, i think, we may[124] assume that they were called after the figure, and that the figure was there before that time.”

“i’m very glad to hear that, sir,” said i. “and then about the scourings and the pastime? they must have been going on ever since the horse was cut out?”

“yes, i think so,” said he. “you have got quotations there from wise’s letter, written in 1736. he says that the scouring was an old custom in his time. well, take his authority for the fact up to that time, and i think i can put you in the way of finding out something, though not much, about most of the scourings which have been held since.”

and he was as good as his word; for he took me about after the pastime to some old men in the neighbouring parishes, from whom i found out a good deal that i have put down in this chapter. and the squire, too, when joe told him what i was about, helped me.

now i can’t say that i have found out all the scourings which have been held since 1736, but i did my best to make a correct list, and this seems to be the proper place to set it all down.

well, the first scouring, which i could find out any thing about, was held in 1755, and all[125] the sports then seem to have been pretty much the same as those of the present day. but there was one thing which happened which could not very well have happened now. a fine dashing fellow, dressed like a gentleman, got on to the stage, held his own against all the old gamesters, and in the end won the chief prize for backsword-play, or cudgel-play, as they used to call it.

while the play was going on there was plenty of talk as to who this man could be, and some people thought they knew his face. as soon as he had got the prize he jumped on his horse, and rode off. presently, first one, and then another, said it was tim gibbons, of lambourn, who had not been seen for some years, though strange stories had been afloat about him.

it was the squire who told me the story about tim gibbons; but he took me to see an old man who was a descendant of tim’s, and so i think i had better give his own account of his ancestor and his doings. we found the old gentleman, a hale, sturdy old fellow, working away in a field at woolstone, and, as near as i could get it, this was what he had to say about the scouring of 1755:—

[126]

squire. “good morning, thomas. how about the weather? did the white horse smoke his pipe this morning?”

thos. “mornin’, sir. i didn’t zee as ’a did. i allus notices he doos it when the wind blaws moor to th’ east’ard. i d’wont bode no rain to day, sir.”

squire. “how old are you, thomas?”

thos. “seventy year old this christmas, sir. i wur barn at woolstone, in the hard winter, when i’ve heard tell as volks had to bwile their kettles wi’ the snaw.”

squire. “i want to know something about your family, thomas.”

thos. “well, sir, i bean’t no ways ashamed of my family, i can assure ’ee. i’ve a got two zons, and vour daaters. one on ’em, that’s my oldest bwoy, sir, wur all droo’ the crimee wars, and never got a scratch. in the granadier guards, sir, he be. a uncommon sprack[25] chap, sir, though i says it, and as bowld as a lion; only while he wur about our village wi’ t’other young chaps, he must allus be a fighting. but not a bad-tempered chap, sir, i assure ’ee. then, sir—”

[127]

squire. “but, thomas, i want to know about those that came before you. what relation was timothy gibbons, whom i’ve heard folks talk about, to you?”

thos. “i suppose as you means my great-grandvather, sir.”

squire. “perhaps so, thomas. where did he live, and what trade did he follow?”

thos. “i’ll tell ’ee, sir, all as i knows; but somehow, vather and mother didn’t seem to like to talk to we bwoys about ’un.”

squire. “thank ’ee, thomas. mind, if he went wrong it’s all the more credit to you, who have gone straight; for there isn’t a more honest man in the next five parishes.”

thos. “i knows your meanings good, and thank ’ee kindly, sir, tho’ i be no schollard. well, timothy gibbons, my great grandvather, you see, sir, foller’d blacksmithing at lambourn, till he took to highway robbin’, but i can’t give ’ee no account o’ when or wher.’ arter he’d been out, may be dree or vour year, he and two companions cum to baydon; and whilst hiding theirselves and baiting their hosses in a barn, the constables got ropes round the barn-yard and lined ’em in. then all dree drawed[128] cuts[26] who was to go out fust and face the constables. it fell to tim’s two companions to go fust, but their hearts failed ’em, and they wouldn’t go. so tim cried out as ‘he’d shew ’em what a englishman could do,’ and mounted his hos and drawed his cutlash, and cut their lines a-two, and galloped off clean away; but i understood as t’other two was took. arter that, may be a year or two, he cum down to a pastime on white hos hill, and won the prize at backswording; and when he took his money, fearing lest he should be knowed, he jumped on his hos under the stage, and galloped right off, and i don’t know as he ever cum again to these parts. then i’ve understood as things throve wi’ ’un, as ’um will at times, sir, wi’ thay sort o’ chaps, and he and his companions built the inn called ‘the magpies,’ on hounslow heath; but i dwon’t know as ever he kep’ the house hisself, except it med ha’ been for a short while. howsomever, at last he was took drinking at a public-house, someweres up hounslow way, wi’ a companion who played a cross wi’ ’un, and i b’live ’a was hanged at newgate. but i never understood[129] as he killed any body, sir, and a’d used to gie some o’ the money as he took to the poor, if he knowed they was in want.”

squire. “thank’ee, thomas. what a pity he didn’t go soldiering; he might have made a fine fellow then!”

thos. “well, sir, so t’wur, i thinks. our fam’ly be given to that sort o’ thing. i wur a good hand at elbow and collar wrastling myself, afore i got married; but then i gied up all that, and ha’ stuck to work ever sence.”

squire. “well, thomas, you’ve given me the story i wanted to hear, so it’s fair i should give you a sunday dinner.”

thos. “lord love ’ee, sir, i never meant nothin’ o’ that sort; our fam’ly”—

we were half-way across the field, when i looked round, and saw old thomas still looking after us and holding the squire’s silver in his hand, evidently not comfortable in his mind at having failed in telling us all he had to say about his fam’ly, of which he seemed as proud as any duke can be of his, and i dare say has more reason for his pride than many of them. at last, however, as we got over the stile, he pocketed the affront and went on with his work.

[130]

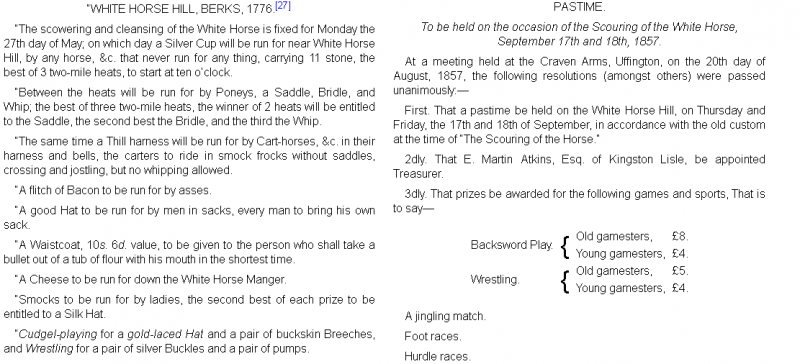

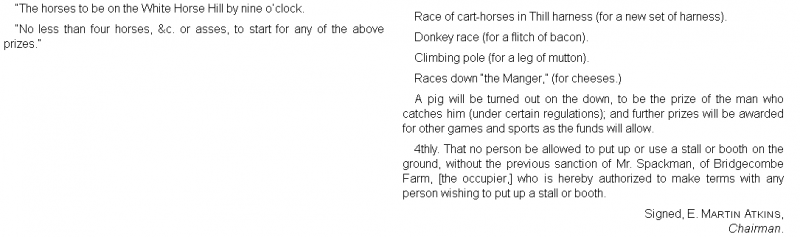

i could find out nothing whatever about the next scouring; but i was lucky enough to get the printed hand-bill which was published before the one in 1776, which i made out to be the next but one after that at which tim gibbons played.

when i showed this old hand-bill to the parson he was very much tickled. he took up the one which the committee put out this last time, and looked at them together for a minute, and then tossed them across to me.

“what a queer contrast,” said he, “between those two bills.”

“how do you mean, sir?” said i; “why the games seem to be nearly the same.”

“so they are,” said he; “but look at the prizes. our great grandfathers, you’ll see, gave no money prizes; we scarcely any others. the gold-laced hat and buckskin breeches have gone, and current coin of the realm reigns supreme. then look at the happy-go-lucky way in which the old bill is put out. no date given, no name signed! who was responsible for the breeches, or the shoe-buckles? and then, what grammar! the modern bill, you see, is in the shape of resolutions, passed at a meeting, the chairman’s[131] name being appended as security for the prizes.”

“that seems much better and more business-like,” said i.

“then you see the horserace for a silver cup has disappeared,” he went on. “epsom and ascot have swallowed up the little country races, just as big manufacturers swallow up little ones, and big shops whole streets of little shops, and nothing but monsters flourish in this age of unlimited competition and general enlightenment. not that i regret the small country town-races, though.”

“and i see, sir, that ‘smocks to be run for by ladies,’ is left out in the modern bill.”

“a move in the right direction there, at any rate,” said he; “the bills ought to be published side by side.” so i took his advice, and here they are:—

then came a scouring on whit-monday, may 15, 1780, and of the doings on that occasion, there is the following notice in the “reading mercury” of may 22, 1780:—

“the ceremony of scowering and cleansing that noble monument of saxon antiquity, the white horse, was celebrated on whit-monday, with great joyous festivity. besides the customary diversions of horseracing, foot-races, &c. many uncommon rural diversions and feats of activity were exhibited to a greater number of spectators than ever assembled on any former occasion. upwards of thirty thousand persons were present, and amongst them most of the nobility and gentry of this and the neighbouring counties; and the whole was concluded without any material accident. the[134] origin of this remarkable piece of antiquity is variously related; but most authors describe it as a monument to perpetuate some signal victory, gained near the spot, by some of our most ancient saxon princes. the space occupied by this figure is more than an acre of ground.”

i also managed to get a list of the games, which is just the same as the one of 1776, except that in addition there was “a jingling-match by eleven blindfolded men, and one unmasked and hung with bells, for a pair of buckskin breeches.”

the parson found an old man, william townsend by name, a carpenter at woolstone, whose father, one warman townsend, had run down the manger after the fore-wheel of a wagon, and won the cheese at this scouring. he told us the story as his father had told it to him, how that “eleven on ’em started, and amongst ’em a sweep chimley and a millurd; and the millurd tripped up the sweep chimley and made the zoot flee a good ’un;” and how “the wheel ran pretty nigh down to the springs that time,” which last statement the parson seemed to think couldn’t be true. but old townsend knew nothing about the other sports.

[135]

then the next scouring was held in 1785, and the parson found several old men who could remember it when they were very little. the one who was most communicative was old william ayres of uffington, a very dry old gentleman, about eighty-four years old:—

“when i wur a bwoy about ten years old,” said he, “i remembers i went up white hoss hill wi’ my vather to a pastime. vather’d brewed a barrel o’ beer to sell on the hill—a deal better times then than now, sir!”

“why, william?” said the parson.

“augh! bless’ee, sir, a man medn’t brew and sell his own beer now; and oftentimes he can’t get nothin’ fit to drink at thaay little beer-houses as is licensed, nor at some o’ the public-houses too for that matter. but ’twur not only for that as the times wur better then, you see, sir——”

“but about the sports, william?”

“ees sir, i wur gandering sure enough,” said the old man; “well now, there wur varmer mifflin’s mare run for and won a new cart saddle and thill-tugs—the mare’s name wur duke. as many as a dozen or moor horses run, and they started from idle’s bush, which wur a vine[136] owld tharnin’-tree in thay days—a very nice bush. they started from idle’s bush, as i tell ’ee, sir, and raced up to the rudge-waay; and varmer mifflin’s mare had it all one way, and beat all the t’other on ’um holler. the pastime then wur a good ’un—a wunderful sight o’ volk of all sorts, rich and poor. john morse of uffington, a queerish sort of a man, grinned agin another chap droo’ hos collars, but john got beaat—a fine bit of spwoort to be shure, sir, and made the folks laaf. another geaam wur to bowl a cheese down the mainger, and the first as could catch ’un had ’un. the cheese was a tough ’un and held together.”

“nonsense, william, that’s impossible,” broke in the parson.

“augh sir, but a did though, i assure ’ee,” persisted william ayres, “but thaay as tasted ’un said a warn’t very capital arter all.”

“i daresay,” said the parson, “for he couldn’t have been made of any thing less tough than ash pole.”

“hah, hah, hah,” chuckled the old man, and went on.

“there wur running for a peg too, and they as could ketch ’un and hang ’un up by the tayl,[137] had ’un. the girls, too, run races for smocks—a deal of pastime, to be sure, sir. there wur climmin’ a grasy pole for a leg of mutton, too; and backsoordin’, and wrastlin’, and all that, ye knows, sir. a man by the name of blackford, from the low countries, zummersetshire, or that waay some weres, he won the prize, and wur counted the best hand for years arter, and no man couldn’t break his yead; but at last, nigh about twenty years arter, i’ll warn[28] ’twur—at shrin’um revel, harry stanley, the landlord of the blawin’ stwun, broke his yead, and the low-country men seemed afeard o’ harry round about here for long arter that. varmer small-bwones of sparsholt, a mazin’ stout man, and one as scarce no wun go where ’a would could drow down, beaat all the low-country chaps at wrastlin’, and none could stan’ agean ’un. and so he got the neam o’ varmer greaat bwones. ’twur only when he got a drap o’ beer a leetle too zoon, as he wur ever drowed at wrastlin’, but they never drowed ’un twice, and he had the best men come agean ’un for miles. this wur the first pastime as i well remembers, but there med ha’ been some afore,[138] for all as i knows. i ha’ got a good memorandum, sir, and minds things well when i wur a bwoy, that i does. i ha’ helped to dress the white hoss myself, and a deal o’ work ’tis to do’t as should be, i can asshure ’ee, sir. about claay hill, ’twixt fairford and ziziter, i’ve many a time looked back at ’un, and ’a looks as nat’ral as a pictur, sir.”

between 1785 and 1803 there must have been at least two scourings, but somehow none of the old men could remember the exact years, and they seemed to confuse them with those that came later on, and though i looked for them in old county papers, i could not find any notice of them.

at the scouring of 1803, beckingham of baydon won the prize at wrestling; flowers and ellis from somersetshire won the prize at backsword play; the waiter at the bell inn, farringdon, won the cheese race, and at jumping in sacks; and thomas street, of niton, won the prize for grinning through horse collars, “but,” as my informant told me, “a man from woodlands would ha’ beaat, only he’d got no teeth. this geaam made the congregation laaf ’mazinly.”

[139]

then came a scouring in 1808, at which the hanney men came down in a strong body and made sure of winning the prize for wrestling. but all the other gamesters leagued against them, and at last their champion, belcher, was thrown by fowler of baydon;—both these men are still living. two men, “with very shiny top-boots, quite gentlemen, from london,” won the prize for backsword play, one of which gentlemen was shaw, the life-guardsman, a wiltshire man himself as i was told, who afterwards died at waterloo after killing so many cuirassiers. a new prize was given at this pastime and a very blackguard one, viz: a gallon of gin or half a guinea for the woman who would smoke most tobacco in an hour. only two gypsy women entered, and it seems to have been a very abominable business, but it is the only instance of the sort that i could hear of at any scouring.

the old men disagree as to the date of the next scouring, which was either in 1812 or 1813; but i think in the latter year, because the clerk of kingstone lisle, an old peninsula man, says that he was at home on leave in this year, and that there was to be a scouring.[140] and all the people were talking about it when he had to go back to the wars. at this scouring there was a prize of a loaf made out of a bushel of flour, for running up the manger, which was won by philip new, of kingstone-in-the-hole; who cut the great loaf into pieces at the top, and sold the pieces for a penny a piece. i am sure he must have deserved a great many pennies for running up that place, if he really ever did it; for i would just as soon undertake to run up the front of the houses in holborn. the low country men won the first backsword prize, and one ford, of ashbury, the second; and the baydon men, headed by beckingham, fowler, and breakspear, won the prize for wrestling. one henry giles (of hanney, i think they said) had wrestled for the prize, and i suppose took too much beer afterwards; at any rate, he fell into the canal on his way home and was drowned. so the jury found, “killed at wrastlin’;” “though,” as my informant said, “’twur a strange thing for a old geamster as knew all about the stage, to be gettin’ into the water for a bout. hows’mever, sir, i hears as they found it as i tells ’ee, and you med see it any[141] day as you’ve a mind to look in the parish register.”

then i couldn’t find that there had been another scouring till 1825, but the one which took place in that year seems by all accounts to have been the largest gathering that there has ever been. the games were held at the seven barrows, which are distant two miles in a southeasterly direction from the white horse, instead of in uffington castle; but i could not make out why. these seven barrows, i heard the squire say, are probably the burial-places of the principal men who were killed at ashdown, and near them are other long irregular mounds, all full of bones huddled together anyhow, which are very likely the graves of the rank and file.

after this there was no scouring till 1838, when, on the 19th and 20th of september, the old custom was revived, under the patronage of lord craven. the reading mercury congratulates its readers on the fact, and adds that no more auspicious year could have been chosen for the revival, “than that in which our youthful and beloved queen first wore the british crown, and in which an heir was born[142] to the ancient and noble house of craven, whom god preserve.” i asked the parson if he knew why it was that such a long time had been let to pass between the 1825 scouring and the next one.

“you see it was a transition time,” said he; “old things were passing away. what with catholic emancipation, and reform, and the new poor law, even the quiet folk in the vale had no time or heart to think about pastimes; and machine-breaking and rick-burning took the place of wrestling and backsword play.”

“but then, sir,” said i, “this last fourteen years we haven’t had any reform bill (worse luck) and yet there was no scouring between 1843 and 1857.”

“why can’t you be satisfied with my reason?” said he; “now you must find one out for yourself.”

the last scouring, in september, 1843, joe had been at himself, and told me a long story about, which i should be very glad to repeat, only i think it would rather interfere with my own story of what i saw myself. the berkshire and wiltshire men, under joe giles of[143] shrivenham, got the better of the somersetshire men, led by simon stone, at backsword play; and there were two men who came down from london, who won the wrestling prize away from the countrymen. “what i remember best, however,” said joe, “was all the to-do to get the elephant’s caravan up the hill, for wombwell’s menagerie came down on purpose for the scouring. i should think they put-to a matter of four-and-twenty horses, and then stuck fast four or five times. i was a little chap then but i sat and laughed at ’em a good one; and i don’t know that i’ve seen so foolish a job since.”

“i don’t see why, joe,” said i.

“you don’t?” said he, “well, that’s good, too. why didn’t they turn the elephant out and make him pull his own caravan up? he would have been glad to do it, poor old chap, to get a breath of fresh air, and a look across the vale.”

but now that i have finished all that i have to tell about the old scourings, (at least all that i expect any body will read,) i must go back again to the kitchen on the night of the 16th of september, 1857. joe, who, as i said, was half[144] asleep while i was reading, soon waked up afterwards, though it was past eleven o’clock, and began to settle how we were to go up the hill the next morning.

“now i shall ride the chestnut up early,” said he, “’cause i may be wanted to help the squire and the rest, but it don’t matter for the rest of you. i’ll have a saddle put on my old brown horse, and he’ll be quiet enough, for he has been at harvest work, and the four-wheel must come up with lu somehow. will you ride or drive, sir?” said he, turning to the parson.

“oh, i don’t mind; whichever is most convenient,” said mr. warton.

“did’st ever drive in thy life, dick?” said joe to me.

i was very near saying “yes,” for i felt ashamed of not being able to do what they could; however, i told the truth, and said “no;” and next minute i was very glad i had, for, besides the shame of telling a lie, how much worse it would have been to be found out by miss lucy in the morning, or to have had an upset or some accident.

so it was settled that mr. warton should drive the four-wheel, and that i should ride the[145] old horse. i didn’t think it necessary to say that i had never ridden any thing but the donkeys on hampstead heath, and the elephant in the zoological gardens. and so, when all was settled, we went to bed.