the directive or versorial virtue (which we call verticity): what it is, how it exists in the loadstone; and in what way it is acquired when innate.

d irective force, which is also called by us verticity, is a virtue which spreads by an innate vigour from the æquator in both directions toward the poles. that power, inclining in both directions towards the termini, causes the motion of direction, and produces a constant and permanent position in nature, not only in the earth itself but also in all magneticks. loadstone is found either in veins of its own or in iron mines, when the homogeneous substance of the earth, either having or assuming a primary form, is changed or concreted into a stony substance, which besides the primary qualities of its nature has various dissimilitudes and differences in different quarries and mines, as if from different matrices, and very many secondary qualities and varieties in its substance. a loadstone which is dug out in this breaking up of the earth's surface and of protuberances upon it, whether formed complete in itself (as sometimes in china) or in a larger vein, is fashioned by the earth and follows the nature of the whole. all the interior parts of the earth mutually conspire together in combination and produce direction toward north and south. but those magnetical bodies which come together in the uppermost parts of the earth are not true united parts of the whole, but appendages and parts joined on, imitating the nature of the whole; wherefore when floating free on water, they dispose themselves just in the same way as they are placed in the terrestrial system of nature. we had a large loadstone of twenty pounds weight, dug up and cut out of its vein, after we had first observed and marked its ends; then after it was dug out, we placed it in a boat on water, so that it could turn freely; then immediately the face which had looked toward the north in the quarry began to turn to the north on the waves and at length settled toward that point. for that face which looked toward the north in the quarry is the southern, and is attracted by the northern

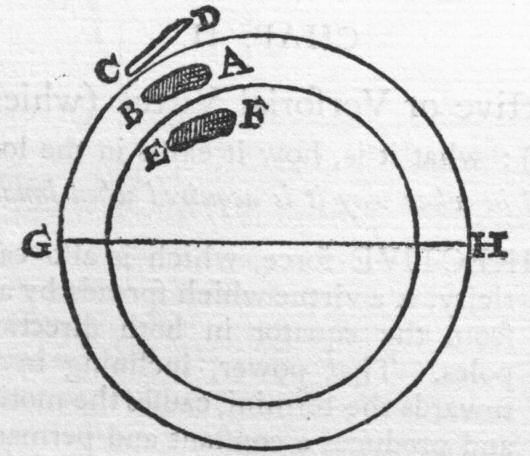

parts of the earth, . in the same way as pieces of iron which acquire their verticity from the earth. about this point we intend to speak afterwards202 under change of verticity. but there is a different rotation of the internal parts of the earth, which are perfectly united to the earth and which are not separated from the true substance of the earth by the interposition of bodies as are loadstones in the upper portion of the earth, which is maimed, corrupt, and variable. let a b be a piece of magnetick ore; between which and the uniform globe of the earth lie various soils or mixtures which separate the ore to a certain extent from the globe of the true earth. it is therefore influenced by the forces of the earth just in the same way as c d, a piece of iron, in the air. so the face b of some ore or of that piece of it is moved toward the boreal pole g, just as the extremity c of the iron, not a or d. but the condition of the piece e f is different, which piece is produced in one connected mass with the whole, and is not separated from it by any earthy mixture. for if the part e f were taken out and floated freely in a boat by itself, it is not e that would be directed toward the boreal pole, but f. so in those substances which acquire their verticity in the air, c is the southern part and is seen to be attracted by the boreal pole g. in the case of others which are found in the upper unstable portion of the earth, b is the south, and in like manner inclines toward the boreal pole. but if those pieces deep down which are produced along with the earth are dug up, they turn about on a different plan. for f turns toward the boreal parts of the earth, because is the southern part; e toward the south, because it is the northern. so of a magnetick body, c d, placed close to the earth, the end c turns toward the boreal pole; of one that is adnate to it b a, b inclines to the north; of one that is innate in it, e f, e turns toward the southern pole; which is confirmed by the . following

demonstration, and comes about of necessity according to all magnetick laws. let there be a terrella with poles a b; from its mass cut out a small part e f; if this be suspended by a fine thread above the hole or over some other place, e does not seek the pole a but the pole b, and f turns to a; very differently from a rod of iron c d; because c, touching some northern part of the terrella, being magnetically carried away makes a turn round to a, not to b. and yet here it should be observed, that if the pole a of the terrella were moved toward the earth's south, the end e of the piece cut out by itself, if not brought too near to the stone, would also move of itself toward the south. but the end c of the piece of iron, placed beyond its orbe of virtue, will turn toward the north. the part e f of the terrella, whilst in the mass, produced the same direction as the whole; but when it is separated and suspended by a thread, e turns to b, and f to a.  so parts having the same

so parts having the same

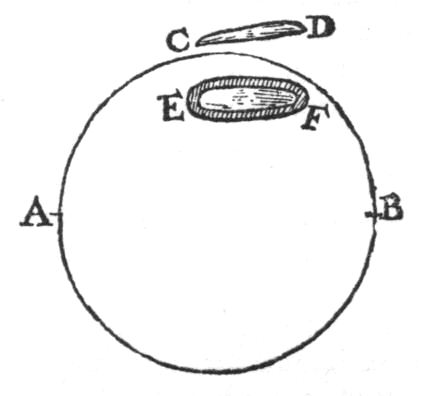

verticity with the whole, when separated, are impelled in the contrary direction; for contrary parts solicit contrary parts. nor yet is this a true contrariety, but the highest concordancy, and the true and genuine conformation of bodies magnetical in the system of nature, if they shall have been divided and separated: for the parts thus divided should be raised some distance from the whole, as will be made clear afterwards. magnetick substances seek a unity as regards form; they do not so much respect their own mass. wherefore the part f e is not attracted into its former bed; but when once it is unsettled and at a distance, it is solicited by the opposite pole. but if the small piece f e is placed back again in its bed or brought close to, without any substances intervening, it acquires its former combination, and, as a part of the whole once more united, accords with the whole and sticks readily in its former position; and e remains toward a, and f toward b, and they settle steadily in their mother's lap. the reasoning is the same when the stone is divided into equal parts through the poles.  a spherical stone is divided into two equal parts along the axis a b; whether therefore the surface a b is in the one part facing upward (as in the former diagram) or lying on its face in both parts (as in the latter), the end a tends toward b. but it must also be understood that the point a is not carried with a definite aim always toward the point b, because in consequence of the division the verticity proceeds to other points, as to f g, as appears in the fourteenth chapter of this book. and l m are now the axes in each, and a b is no longer the axis; for magnetick bodies, as soon as they are divided, become single magnetick wholes; and they have vertices in accordance with their mass, new poles arising at each end in consequence of the division. yet the axis and the poles always follow the leading of a meridian; because that force passes along the meridians of the stone from the æquator to the poles, by an everlasting rule, the inborn virtue of the substance agreeing thereto from the long and lasting position and the facing of a suitable substance toward the poles of the earth; by whose strength continued through many centuries it has been fashioned; toward fixed and determined parts of which it has remained since its origin firmly and constantly turned.

a spherical stone is divided into two equal parts along the axis a b; whether therefore the surface a b is in the one part facing upward (as in the former diagram) or lying on its face in both parts (as in the latter), the end a tends toward b. but it must also be understood that the point a is not carried with a definite aim always toward the point b, because in consequence of the division the verticity proceeds to other points, as to f g, as appears in the fourteenth chapter of this book. and l m are now the axes in each, and a b is no longer the axis; for magnetick bodies, as soon as they are divided, become single magnetick wholes; and they have vertices in accordance with their mass, new poles arising at each end in consequence of the division. yet the axis and the poles always follow the leading of a meridian; because that force passes along the meridians of the stone from the æquator to the poles, by an everlasting rule, the inborn virtue of the substance agreeing thereto from the long and lasting position and the facing of a suitable substance toward the poles of the earth; by whose strength continued through many centuries it has been fashioned; toward fixed and determined parts of which it has remained since its origin firmly and constantly turned.